Postpartum

Feb 04, 2026

Simona Byler

5 min

When talking about childbirth, people often whisper about getting a “tear” or having to get stitches afterward, which can sound pretty scary! If you have heard of a “Grade II tear” or “Grade III tear” while giving birth, or experienced it yourself, this refers to perineal tears, or injury to the tissue between the vagina and the anus. The grades are based on the size and depth of the injury.

However, there is another type of pelvic muscle tear that can also occur, deeper in the pelvis, that often goes undiagnosed and untreated. They are called levator ani injuries, tears or avulsions (where muscle comes away from the bone). Research shows these injuries happen in roughly 10-30% of vaginal births,and yet most people have never heard of them!

Levator ani injuries can cause issues right after birth or years down the line. If you're preparing for delivery, understanding this injury can help you make informed decisions about your birth and postpartum care. If you're postpartum and dealing with symptoms like pelvic heaviness, bladder leakage, or pain during sex after giving birth, this could be why. The good news is, with the right treatment, these symptoms can improve!

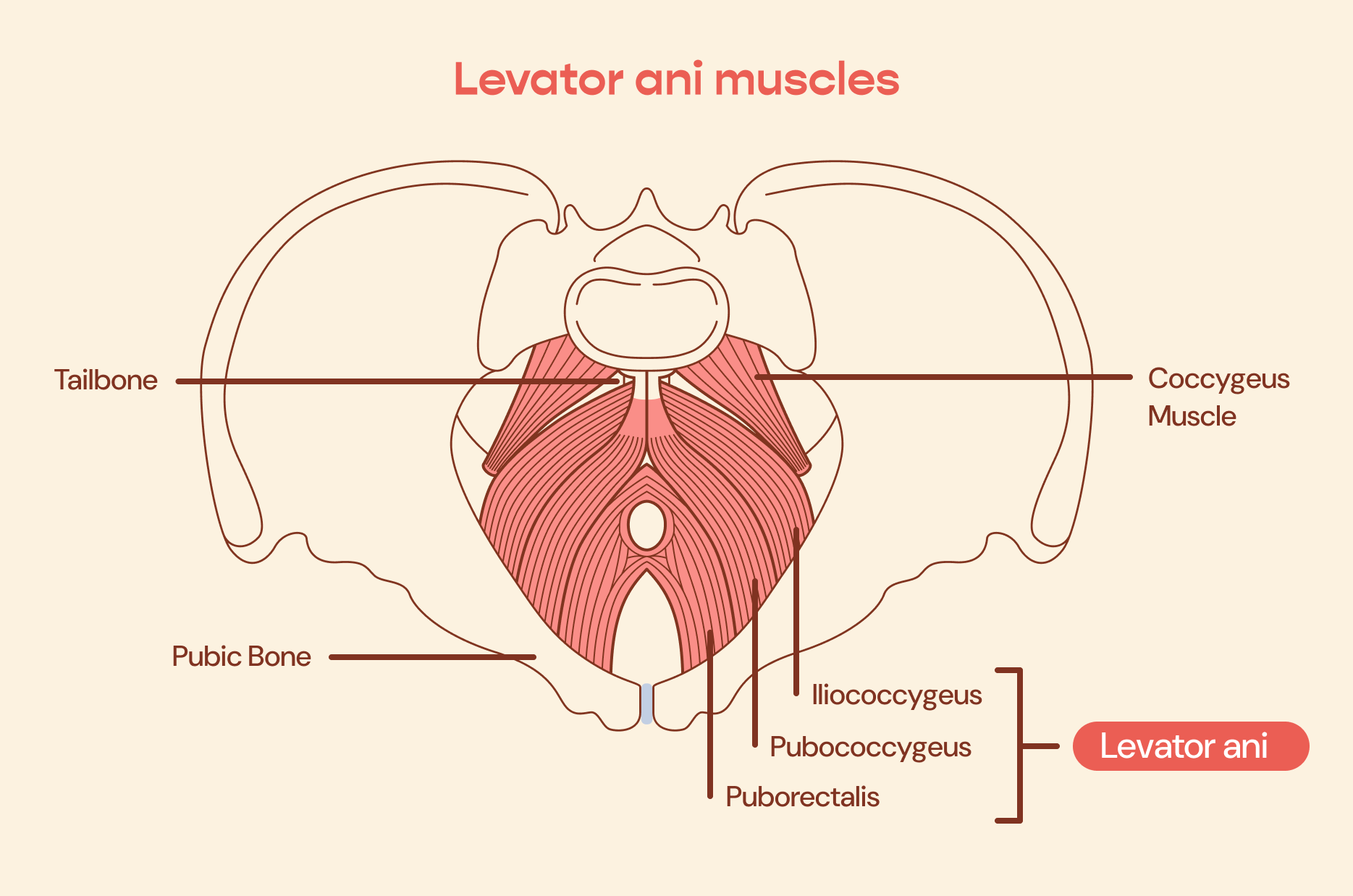

The levator ani are a group of muscles at the base of the pelvis. They support your pelvic organs (including your bladder, rectum, and uterus) and help with bladder and bowel control, sexual function, and core stability. These muscles form a funnel shape that stretches from your pubic bone in front to your tailbone in back, connecting at your sit bones on either side. The rectum, vagina, and urethra all pass through them. When you engage these muscles (like when you're trying to stop the flow of urine), they lift the pelvic floor upward—that's actually where the name comes from ('levator' means 'to lift').

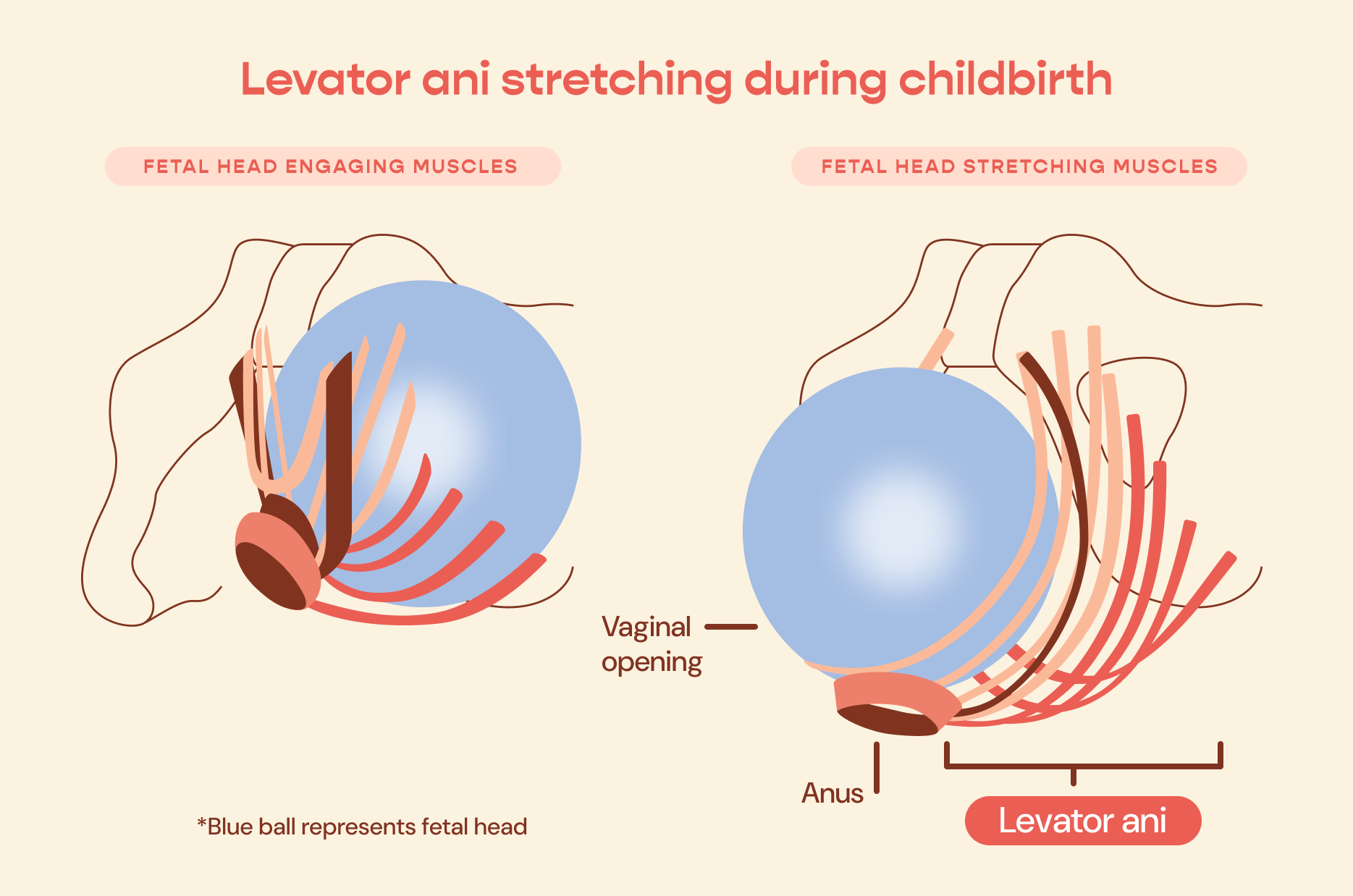

During the “pushing” phase of labor (also called the second stage), your levator ani muscles stretch significantly as your baby moves through the birth canal. We're talking about stretching up to 3.3 times their resting length; that's far more than most muscles in your body can handle! While this extreme stretch is pretty amazing, it also puts these muscles at risk. Unlike perineal tears that happen on the surface where you and your healthcare provider can see them, levator ani injuries occur deeper in your pelvis. In more severe cases, the muscle may completely separate from the bone in places (this is called "levator ani muscle avulsion").

Here's some hopeful news: research suggests that about half of people who experience this type of tear will recover within a year of giving birth. However, if you're in the other half and your symptoms don't resolve on their own, they can significantly impact your quality of life. That's where treatment comes in, and pelvic floor therapy is an excellent place to start.

There are a wide range of estimates of how common levator ani injuries are, with studies reporting somewhere between 10-30% of all vaginal deliveries. Certain birth interventions can increase your risk, particularly the use of forceps and vacuum assistance. Other factors that may increase your risk include having a longer pushing phase, delivering a baby with a larger head size or birthweight, having a lower BMI, occiput posterior birth position (when your baby is “face up,” sometimes called “sunny side up”), and increased maternal age. On the other hand, having an epidural and increased BMI of the birthing person seem to be protective factors for levator ani injuries. It’s also important to know that if you end up having a Cesarean section after you've already been pushing, you could still have this injury.

Additional factors that may increase risk but are usually only measured in a research setting include the starting length of the muscles, stretchiness of the tissues involved, the shape of the pubic bones in the front of the pelvis, as well as the degree to which the baby’s head “molds” into a cone shape. However, even with some of these known risk factors, whether or not someone gets this injury can still be unpredictable, which is why it is important to get checked out if you are concerned!

This is a tricky question, because preventing levator ani injury during birth may not always be avoidable. However, there are some steps you might consider that could help:

If you've had this type of injury, you might experience symptoms like:

You can also have some of these symptoms without a levator ani injury, and you could also have an injury without experiencing all these symptoms.

Some physical therapists and OB/GYNs with special training can detect a levator ani avulsion during a vaginal exam, but the most definitive way to diagnose it is with an ultrasound. If you're wondering whether you have this injury, talk to your doctor about getting an exam.

Like many injuries, the impact of a levator ani injury can range from causing no symptoms at all to creating issues that affect your daily life. The most common complication is pelvic organ prolapse (POP), when one of your pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, or rectum) pushes into your vaginal canal. In some cases, it can extend out of the vaginal opening.

Mild prolapse is actually extremely common and often doesn't cause any symptoms. However, if you're experiencing a visible or felt bulge that makes it difficult to pee or poop, or if you have uncomfortable pressure or pain, it's worth addressing. If you're considering surgery for prolapse, it's important that your doctor rules out a levator ani avulsion first. If the underlying muscle injury isn't addressed, you could experience a recurrence of the prolapse after repair.

Pelvic floor physical therapy: If you're having symptoms that bother you, this is an excellent first step. A pelvic floor therapist can help you strengthen your pelvic floor muscles, reduce painful tension, and improve coordination of the surrounding muscles to compensate for the injury. They can also help you troubleshoot issues with bowel movements, bladder function, or sexual activity. Book your virtual or in-person evaluation today!

Other options if PT isn't enough: If your symptoms aren't improving with physical therapy alone, there are additional options. For prolapse symptoms, you might try a pessary (a supportive device that's inserted into your vagina). There are also surgical options, which can repair or reattach the levator ani muscles or address prolapse. The best surgical approach for you will depend on how severe your prolapse is, what type of avulsion you have, and your surgeon's expertise.

If you've experienced a levator ani injury or any other birth injury or trauma, please know that you're not alone. The first step is recognizing what's happening so you can get proper treatment and support. These issues can feel difficult to talk about, but by being informed and advocating for yourself, you can access the care you deserve.

Alketbi, M S Gh et al. “Levator ani and puborectalis muscle rupture: diagnosis and repair for perineal instability.” Techniques in coloproctology vol. 25,8 (2021): 923-933. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02392-6

Dietz, H.P., Moegni, F. and Shek, K.L. (2012), Diagnosis of levator avulsion injury: a comparison of three methods. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 40: 693-698. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.11190.

Cassadó, J. et al. "Prevalence of levator ani avulsion in a multicenter study (PAMELA study)." Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 302 (2020): 273-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05585-4.

Delancey, J. et al. "Pelvic floor injury during vaginal birth is life-altering and preventable: what can we do about it?." American journal of obstetrics and gynecology (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.11.1253.

Doxford-Hook E. et al. "Management of levator ani avulsion: a systematic review and narrative synthesis." Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 308 (2023): 1399 - 1408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-06955-4.

Handa et al. "Pelvic Floor Disorders After Obstetric Avulsion of the Levator Ani Muscle." Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 25 (2019): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0000000000000644.

Kamisan Atan, I., Lai, S.K., Langer, S. et al. The impact of variations in obstetric practice on maternal birth trauma. Int Urogynecol J 30, 917–923 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03887-z.

Lien, Kuo-Cheng et al. “Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth.” Obstetrics and gynecology vol. 103,1 (2004): 31-40. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000109207.22354.65

Tracy, Paige V et al. “A Geometric Capacity-Demand Analysis of Maternal Levator Muscle Stretch Required for Vaginal Delivery.” Journal of biomechanical engineering vol. 138,2 (2016): 021001. doi:10.1115/1.4032424